If discretion is the greater part of valour, then Bernard Lederer may be among the most chivalrous watchmakers working today. Even if you’re familiar with the auction defining likes of F. P. Journe and Philippe Dufour, there’s a good chance that you’ve not come across the independent watchmaker’s name, let alone his watches. And there’s a good reason for that.

When a major watch house – or fashion company with a serious watch collection, let’s say – has an intense horological concept they want to create, they tend not to do it in-house. Even if they do have their own watchmaking studios (and that’s a big ‘if’), they simply won’t have someone on hand to turn a designer’s mechanical fever dream into reality. That’s why many of them turn to Bernard Lederer, a problem-solving watch designer that, due to the marketing necessity of confidentiality, rarely actually comes to the fore.

It’s perhaps misleading therefore to look at Bernard Lederer’s back catalogue and only take into account the creations with his name on. Consider them just the tip of a very large, very secretive iceberg. But given the magnitude of what Lederer has achieved, you can be sure there’s a lot of hidden ice under the surface.

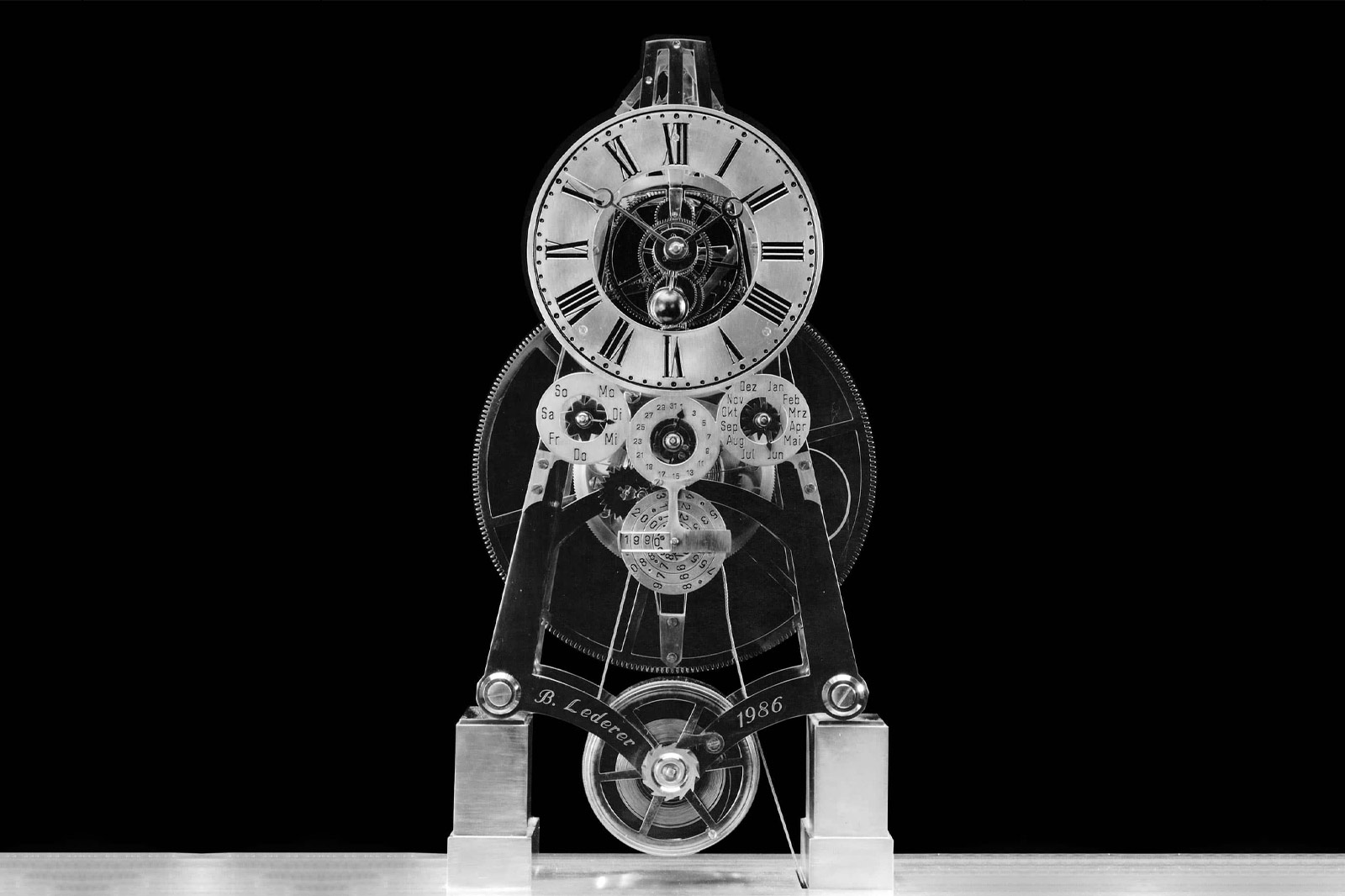

Lederer Masterpiece Table Clock (1986)

For one, German-born Lederer is a founding member of the AHCI, the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants, an association of the finest independent watch and clockmakers working today. For another, the projects we have seen have been historically magnificent. His Masterpiece table clock in 1986 (a year after the AHCI was founded) included a 1,000-year calendar, gravity escapement and temperature differential like a souped-up Harrison Marine Chronometer you can find in the Greenwich observatory. He even built the giant 1996 clock counting down to Brazil’s 500th anniversary of discovery, designed to survive intense heat, dust and elements less than kind to accurate timekeeping.

Bernard Lederer White Gold Blu MT3 Majestic Tourbillon (2010), image credit: Christie’s

On the wristwatch side, in 2007 he created the MT3 Tourbillon, which consisted of three cage-free (free-range) tourbillons supported by a single bridge. In 2011, he followed-up with the Gagarin tourbillon, an ode to the legendary Russian cosmonaut, which features a counter clockwise-moving flying tourbillon that makes one revolution every 108 minutes – the length of Gagarin’s historic space flight.

So, while he doesn’t necessarily do much that’s visible to the average consumer, when Lederer does work on a project, you know it’s going to be something astounding. What’s perhaps unusual then is that the watchmaker’s true obsession isn’t tourbillons or clocks, but one small yet vital element of a movement: the escapement.

The movement inside the Lederer Central Impulse Chronometers uses Lederer’s revolutionary escapement

First a bit of watchmaking 101. Energy in a watch movement comes from the mainspring, the bit you actually wind. This is then transferred to the balance, the oscillator that breaks up that energy into measurable time. Part of how it does that is the spring that coils and uncoils, but the less spoken about part is the escapement. This consists of a pallet fork, which you can usually see due to its rubies and an escape wheel. As the balance spring oscillates back and forth, it pushes the pallet fork from one side of the escape wheel to the other, allowing the geartrain to move forward, before locking back into place and sending an impulse back to the balance, starting the process again. This movement then feeds into the rest of the watch and you have timekeeping.

That’s very brief and likely to give any watchmakers reading this a migraine, but that’s it in layman’s terms. The escapement is also something that over the past centuries has been relatively untouched. Indeed, Breguet played with the idea as he did with most watchmaking concepts, but the only real advances in the last century came from George Daniels and the Co-Axial escapement that’s now a part of most Omega movements.

Lederer Central Impulse Chronometer Red Gold

Lederer’s story goes that after inheriting his grandfather’s pocket watch, he read a book on the sound patterns of various escapements (the tick-tock of a watch is the rubies of the pallet fork clacking into place), he added a special escapement to his first self-made piece. Since then, he’s stood on the shoulders of giants – specifically the giants Breguet and Daniels – to become the greatest luminary of escapements in the world. Case in point, the Central Impulse Chronometer.

Bernard Lederer’s Central Impulse Chronometer is a magnificent piece of true watchmaking. The actual changes to what I briefly outlined above are enormous and the technicalities are worth an essay in and of themselves. Much as I want to keep you reading these pages, if you’re interested, plenty of digital ink has been spilled on the subject, if you can parse the technicalities.

The newest addition to the CIC range is the Lederer Central Impulse Chronometer 39mm with 18% reduction in the movements thickness, limited to 20 pieces each colourway

The brief summation is that Lederer has combined Breuget’s Natural Escapement, a double-wheel number that was designed to work without oil, and George Daniel’s Independent Double Wheel Escapement. This latter involves having two balance wheels that alternately interact with the escapement. The amount of effort funnelled into marrying the two is mind-blowing – patents and innovations aplenty – but the result is one of the most efficiently running movements ever built. It not only has two balance wheels, but it has two independent barrels, two independent constant-force mechanisms (remontoires) and two independent gear trains!

While, like many an independent watchmaker, Bernard Lederer’s all about the minute mechanics and perfecting chronometric performance, it also can’t go unsaid that the Central Impulse Chronometer is an absolute stunner. There’s something to be said for the twin visible balances on display and the finishing across the rest of the watch is invariably on par – if pared-back in a typically German way – with the finest independent watchmakers out there. It’s gorgeous, understated and necessarily limited (to 20 pieces in the latest version). The fact you can still get them on occasion shows that Bernard Lederer is still not as well-known as he very much should be. Here’s hoping this goes some minute way towards changing that.

More details at Lederer.